Core Platform Objects

In this section we'll examine the basic building blocks of DNN from a technical perspective and see how they fit together.

Portals/Sites

DNN is a powerful engine for creating websites. That is websites, plural not singular. One of DNN's core features is what is known as "portal virtualization". That is: a single DNN instance can serve multiple discrete websites. An instance, here, is synonymous with a DNN installation. I.e. the files that you've copied to your server's DNN folder with a web.config file in the root (TIP: a universal way to spot a .net web application is the web.config in its root directory). The aforementioned websites are known as portals. Portal is the DNN API name for what you'd call a website or simply a site. It stems from the very first version of DNN and an era where you had several popular internet portals like Yahoo that aggregated content from other websites. The visual and textual language of DNN is rooted in this time, hence the term Portal to describe a site.

So DNN can have multiple sites. But a single site can have multiple aliases. A Portal Alias is a fancy term for url, albeit technically more accurate. So a single site can appear as http://www.acme.com and http://acme.com as well as http://public.acme.com. Whenever a request is made to your server, IIS is responsible for routing the various urls (or domains as they're often called) to the correct applications. And your server's administrator would be responsible for making sure all these urls map to the DNN instance. After that, it's DNN that must decide which portal to serve based on the incoming url. So for each portal you can specify multiple portal aliases to let DNN route multiple urls to the same website.

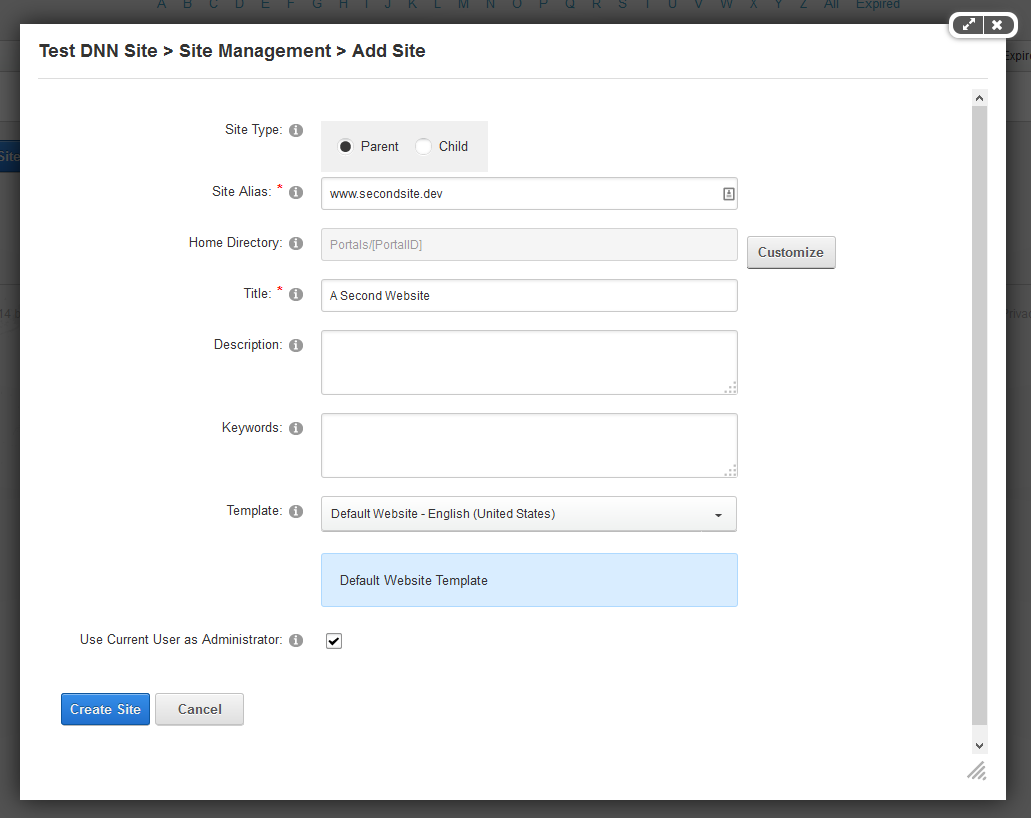

If you look at the page where you specify a new portal (you'll find this under Site Management on the Host menu), you'll notice that there are two types of portal ("Site Type"): a parent portal and a child portal. These terms can be somewhat confusing as the child portal is not embedded within the parent portal at all. Instead, the only difference is in the form of the portal alias. Parent portals have at least one unique domain. So the urls mentioned above are all for parent portals. Child portals, on the other hand are defined like subdirectories of a domain. So a child portal given the above installation could be http://www.acme.com/public. Now the "public" portal is defined as a child portal. Still, all its data is kept strictly separate from http://www.acme.com (if that were a parent portal on the same installation).

So why would we use child portals? Well, there are a couple of scenarios where this is useful. The first concerns cookies. Browsers typically protect the user's privacy by blocking any website from accessing cookies set by other websites. So a cookie set by Google cannot be read by Apple and vice versa. You can see where I'm going with this. The child portal's cookies will be accessible by the parent portal and vice versa. Crucially, this makes it possible to keep a user logged in (login status relies on cookies). So if a user has been shared between a parent and a child portal, that user could navigate between the two sites and not have log in every time he/she switches (so-called "single sign-on"). A second reason for child portals is one of access rights. For a new parent portal you need to add the new domain to IIS and to a DNS record. The person who is allowed to create new portals might very well not have that authority/access. So in that case a child portal is an alternative to create a new site without the necessity to access other company resources.

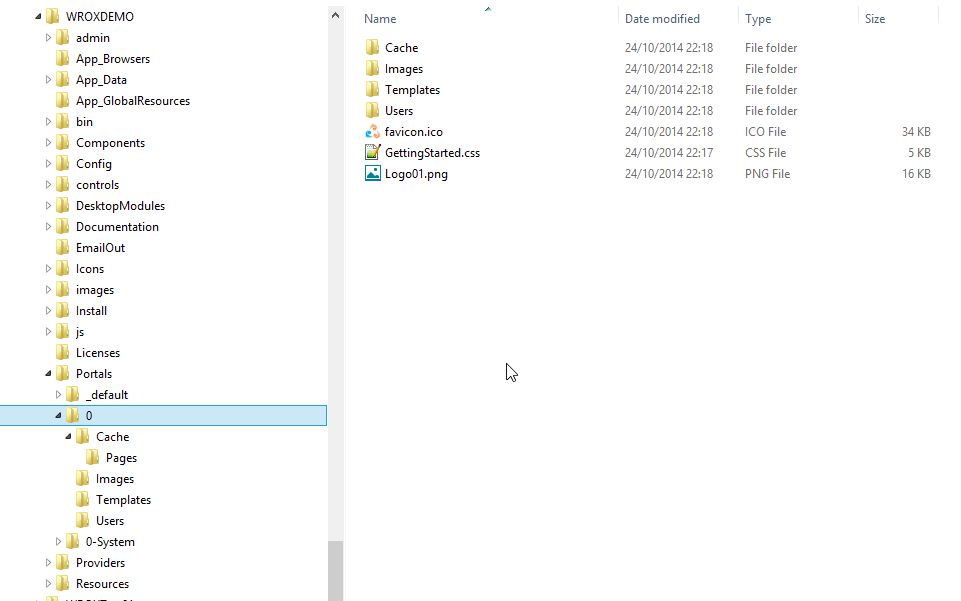

The data for each portal can be divided in two parts: database data and file data. The former is stored in the various tables of your DNN database and the latter is stored in some file based storage location and called the Home Directory. By default this is found in the directory portals/[PortalID] of your installation. You can specify another location on your server's hard disk and since version 7.3 of DNN you can specify alternate (cloud based) locations for this storage (and you could even extend the framework and build your own provider for this but now I'm drifting off topic). The point of this paragraph is that you realize that the files for each portal are stored in discrete folders somewhere. And DNN makes sure that no files "leak" from one portal to another. Your portals are thus really discrete entities inside the framework. This is crucial if you think of the following use case. As a successful developer you have created a DNN installation that is perfectly tuned to serve small businesses in your local area with a website. For each customer you create a new portal: http://www.joeplumbing.com, http://www.jilldrycleaning.com, etc, etc. But you need to have peace of mind that the content of these sites is secured from each other. Knowing how DNN organizes content will give you this peace of mind.

Finally you should know that each portal has a unique Portal ID and GUID. The Portal GUID (Globally Unique IDentifier) is a relatively new addition but it's the Portal ID that is used throughout the framework to identify a portal. You'll find numerous tables in SQL have a column PortalID that refers back to the portal (stored in the Portals table). And by default the PortalID is used in the creation of the subdirectory under portals for the portal home directory.

Tabs/Pages

Each website consists of a number of pages. Or to put it in DNN parlance: each portal has a number of tabs. The word Tab stems from the project that DNN was originally derived from: IBuySpy. In that sample project, Microsoft demonstrated how you could build a website using a tabbed layout. The term for page is thus Tab in the DNN API. Back in the bad old days of static websites (so before the wide-scale adoption of CMSs), the pages of a website were all discrete files (often .html files) on your web server. So typically there'd be a file index.html which would be served by the web server when the browser was first directed at the site. Then any page would be simply point to a file on the web server. Since the introduction of web applications like DNN we have parted with this way of doing websites. Instead the html that is served to the browser is built up on the fly by the web application on the server and sent immediately to the client. No html file exists any longer that stores that html that was served. Instead the application typically uses some form of templates that are subsequently filled with data from a database. In this way we can show a "Hello Peter" page when Peter is logged in and a "Hello Shaun" page when Shaun is logged in.

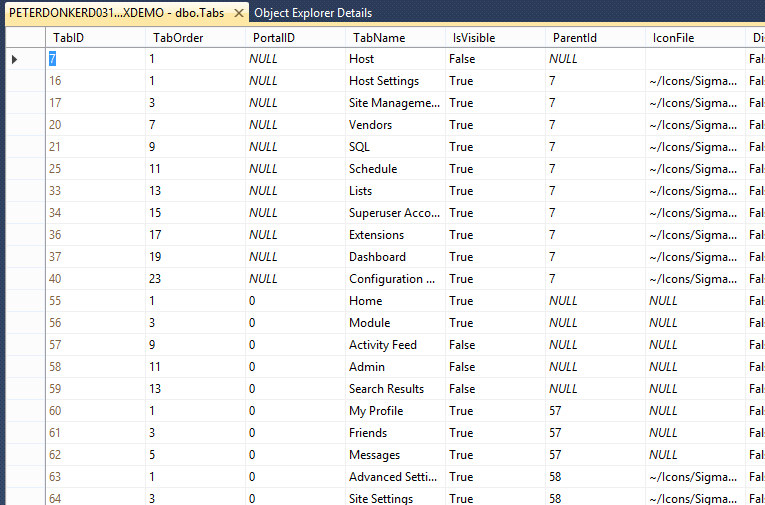

The various tabs are stored in the Tabs table in the SQL database. And just like portals, tabs have a unique Tab ID (an auto incrementing integer) and GUID (called UniqueID in the table), but the TabID is used throughout the framework to identify them.

A web application like DNN includes logic to generate and interpret urls as the pages are no longer files on disk. This is not a trivial matter. Urls are crucial to SEO for instance, so you'll find many are very opinionated about this aspect of the framework. To cater for any scenario DNN has detached this part of the application so anyone can write their own version. The generic term for this is "url rewriter". A url rewriter constructs urls that are displayed in the application than can then be subsequently interpreted by it and mapped to a specific tab ID. The first versions of DNN did not include much url rewriting and you would have seen urls like this: http://www.acme.com?tabid=32. As you can probably guess this url would show the tab with id 32. But in essence all url rewriters that exist even today just translate the incoming url (e.g. http://www.acme.com/products/dynamite) to something similar to that raw url with tabid=xyz that is then used internally to find the right tab.

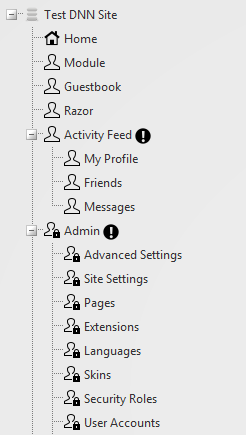

Tabs are organized in a tree. That is: they can be nested. In the Tabs table you'll see the ParentID value that points to the TabID value of the parent tab. This is how most modern websites are currently structured. Any page sits somewhere in a tree hierarchy. And ideally the url rewriter uses this hierarchy to create "human friendly" urls that reflect this by using the titles as if they were subdirectories. So the aforementioned url would point to a page with the title "dynamite" underneath the page with the title "products". This makes sense not just to humans but it's greatly rewarded by Google as well in your ranking.

Skin

Every tab has a setting telling DNN which skin to load to display it. The skin defines how various elements are positioned on the page and how they look. In other frameworks this is sometimes referred to as a theme. The DNN Platform aims to separate the concerns of programmers, designers and content managers as much as possible. So designers should be able to do their job independently from programmers for instance. What this means is that you can change the look and feel of a site without changing its functionality or content.

A skin is typically comprised of some html template file (.ascx), javascript files and css files. And a single skin package can contain multiple of these skin templates. Often you'll find a template for the home page, for an admin page and for a regular (default) page. The home page would then include some extra space for a banner/image slider for instance. In the site settings you can specify the default skin to use for the site, but any page can override this setting and specify its own special skin to use.

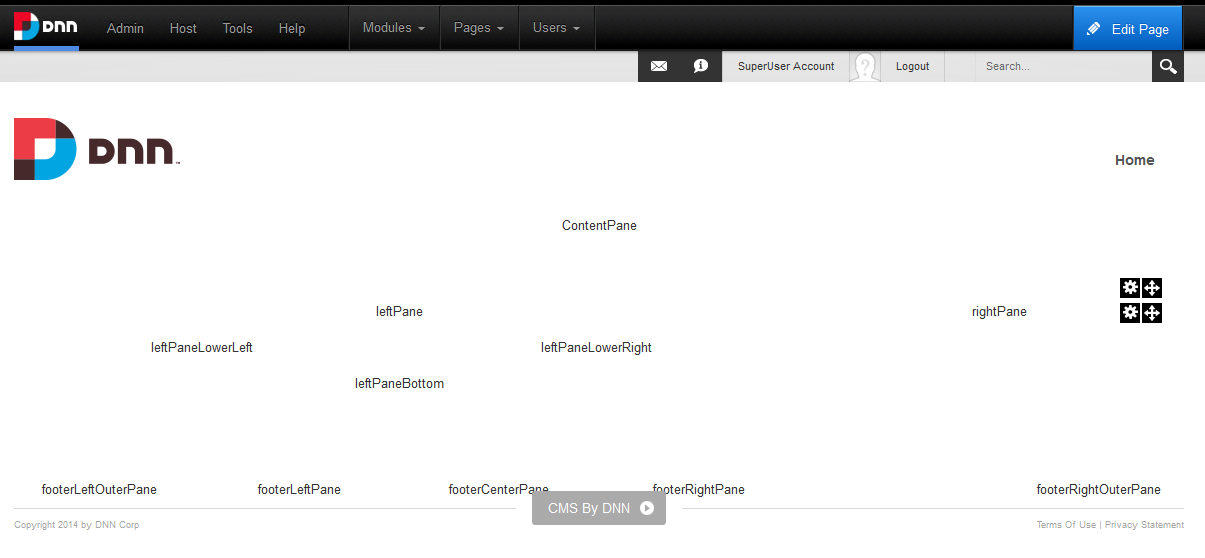

The most important element on a page is undoubtedly the one responsible for navigation; i.e. the menu. Other common elements are the logo and the banner for the site as well as the footer elements such as copyright messages and disclaimers. Obviously DNN will also need to know where to put the page's contents. For this the skin template defines a set of panes. Panes are essentially div elements that have been given a meaningful name by the designer: LeftPane, RightPane, BannerPane, etc. These names will show up in the UI and allow the user to specify where something will be added on the page. If you switch to Layout Mode (use the top right menu on the control bar) you'll see all these panes light up and you will see how the designer has subdivided the page for you.

Modules

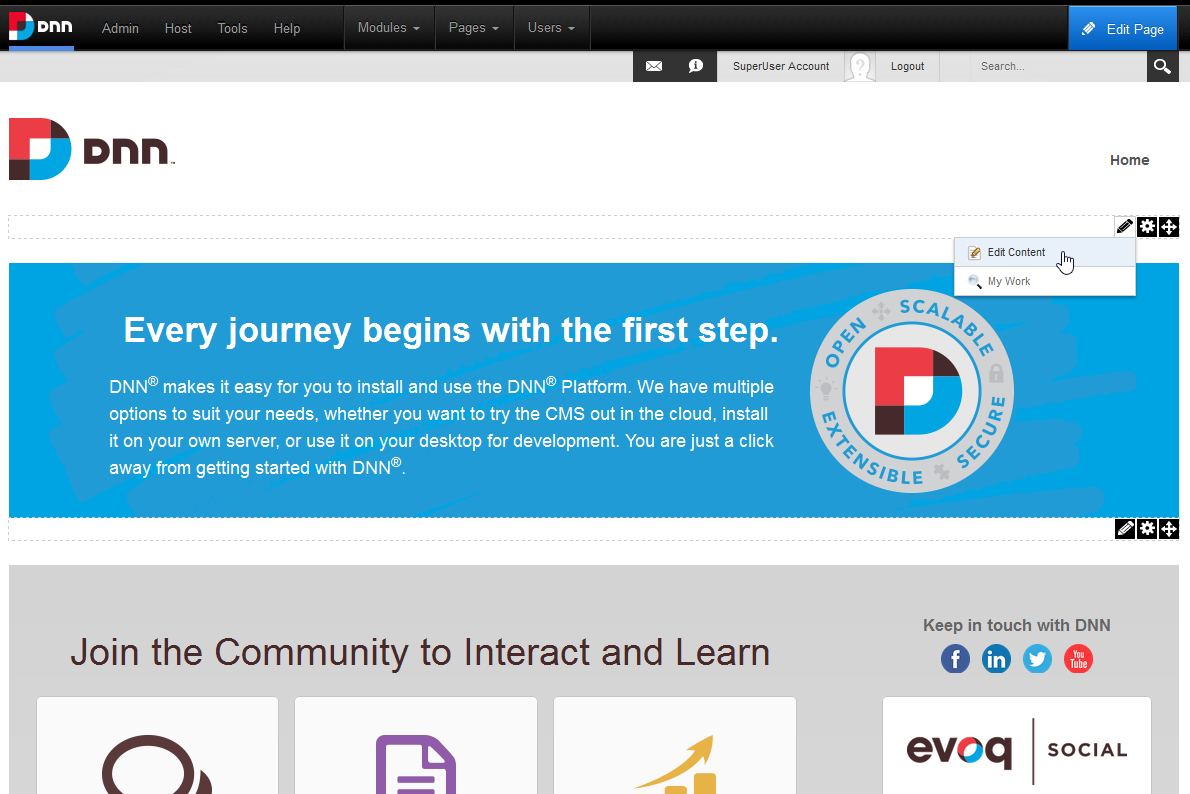

Each tab in DNN displays any number of modules. Modules are basically the rectangular blobs you see spread on the page's surface and that each have a small menu when you switch to edit mode (to switch the mode go to the top right hand side of the page on the control bar).

These modules are what makes the site tick. They are the fundamental building blocks of functionality of your site. You can have a module that displays a block of text (the most common module by far) but you can also have a module that shows a small calendar with events or a module that displays a list of (recent) news articles. And it all began with what has been dubbed "Web 2.0". That is: the web is no longer a collection of static texts and images, but rather an interactive surface that allows people to modify its contents. Modules are the "apps" of the web. They perform a particular function (e.g. manage an event calendar). And it is one of the most important extension points of DNN. That is: you can create your own modules (explained elsewhere in this book) and let the users stick that on any page of their site. And the ease with which this can be done and the power it provides the developer is the number 1 reason for DNN's success.

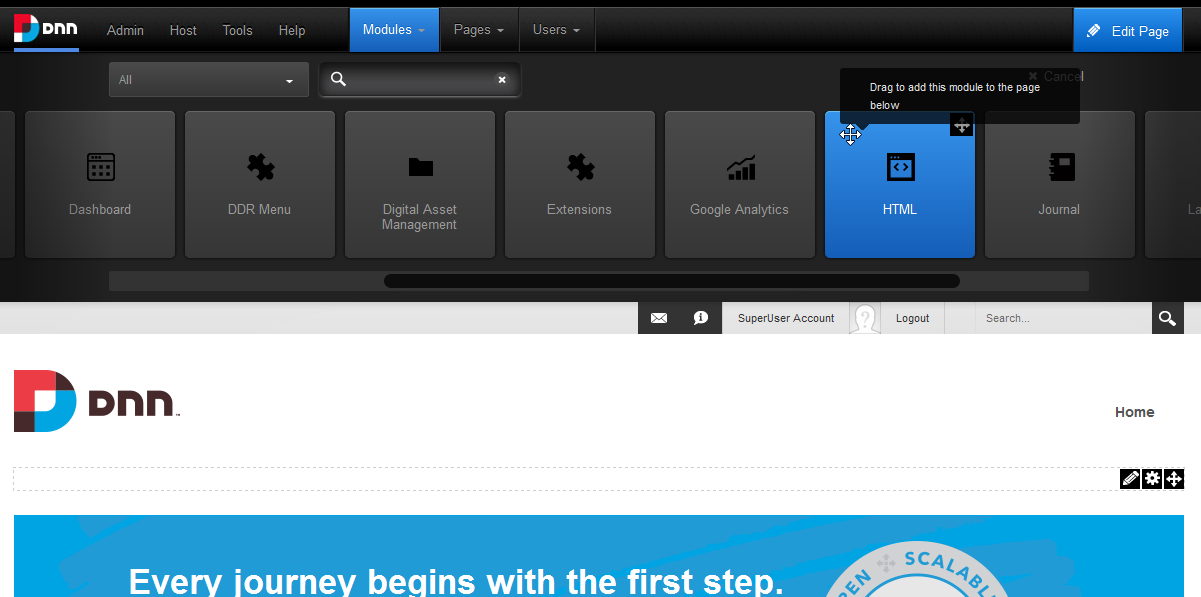

Modules are instantiated on a page through the "module" tab on the control panel. If you click "Add Module" a list of installed modules will show and you can drag and drop those onto your page surface. Typically you will then set some parameters like who can edit its contents and some generic parameters that concern the specifics of the module (e.g. whether to render a calendar or a chronological list of events). This is commonly referred to as the Module Settings and this can be accessed through the little menu that shows up when you are in edit mode (see fig 3-6).

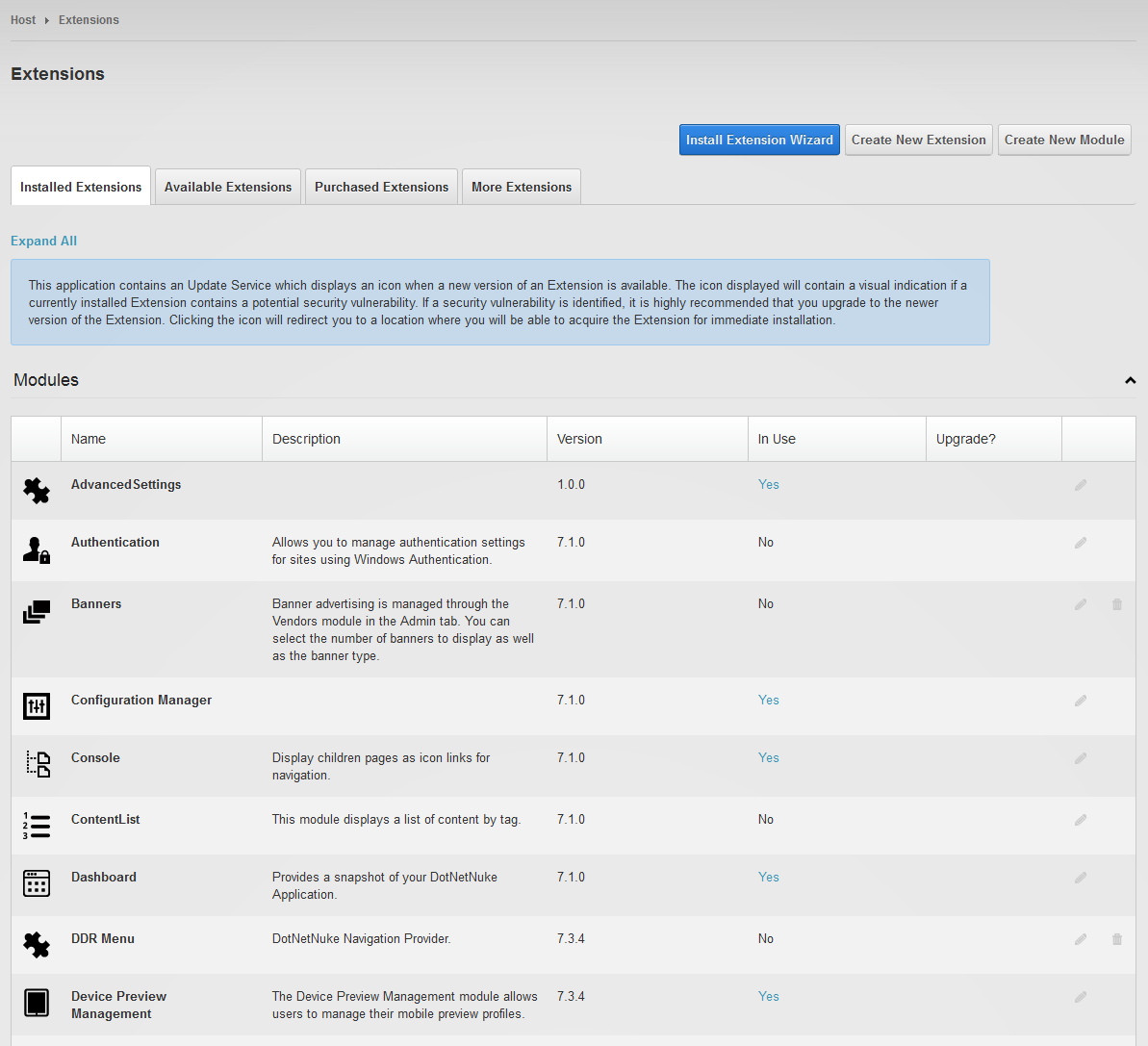

The installed modules on your DNN installation are managed on the "Extensions" page on the host menu. Here you will see what is installed, what is ready to install (has already been downloaded) and you can access the DNN Store for more modules (both free and commercial).

The first time you see the list of installed modules it may seem overwhelming. But most of those are administrative modules that you cannot (and should not) delete. They are part of the framework. Using the "Install Extension Wizard" button at the top of the page you can also install modules that you've downloaded (or created) and bypass the DNN Store. This is not a closed system like most mobile platforms. And you'll find hundreds of free (and often open source) modules on sites like Codeplex and Github. A module is delivered as a zip file. All you need to do is upload the zip file through the Extensions page and DNN takes care of the rest. This process has been made as easy as possible for both the administrator and the developer. Even upgrades are taken care of automatically. Just upload the zip file you've downloaded and the module will appear on the control bar so it can be dropped onto a page.

When a module gets added to a pane it is wrapped inside what is known as a container. This is similar to a skin in that it is defined by the designer and is a template file that tells DNN how the module is wrapped. The container typically determines how the title of the module is rendered. And it can be used to draw a border around a module or give it an alternate background color. Containers are typically distributed along with the skin. And just like the skin you'll have a default container for the site and the ability to override the default for each module.

Note

This is an extract from the Wrox book Professional DNN 7 by Shaun Walker et al. Copyright remains with P.A. Donker and Wiley Publishers.